Fibonacci in Plonky3 - Introduction to Plonky3¶

Understanding Plonky3¶

Plonky3 is a toolkit for designing a custom ZK proving implementation that can then be used to power application-optimized zkVMs and zkEVMs.

In the same way an AI dev uses Pytorch and Tensorflow for building AI models, Polygon Plonky3 provides the same flexibility for building ZK proving systems. Polygon Plonky3 enables simple builds, such as the Fibonacci sequence prover in this repo that requires only one AIR Script, to complex systems, such as SP1 from Succinct labs with multiple AIR scripts for different components of a single zkVM.

How does Plonky3 work?¶

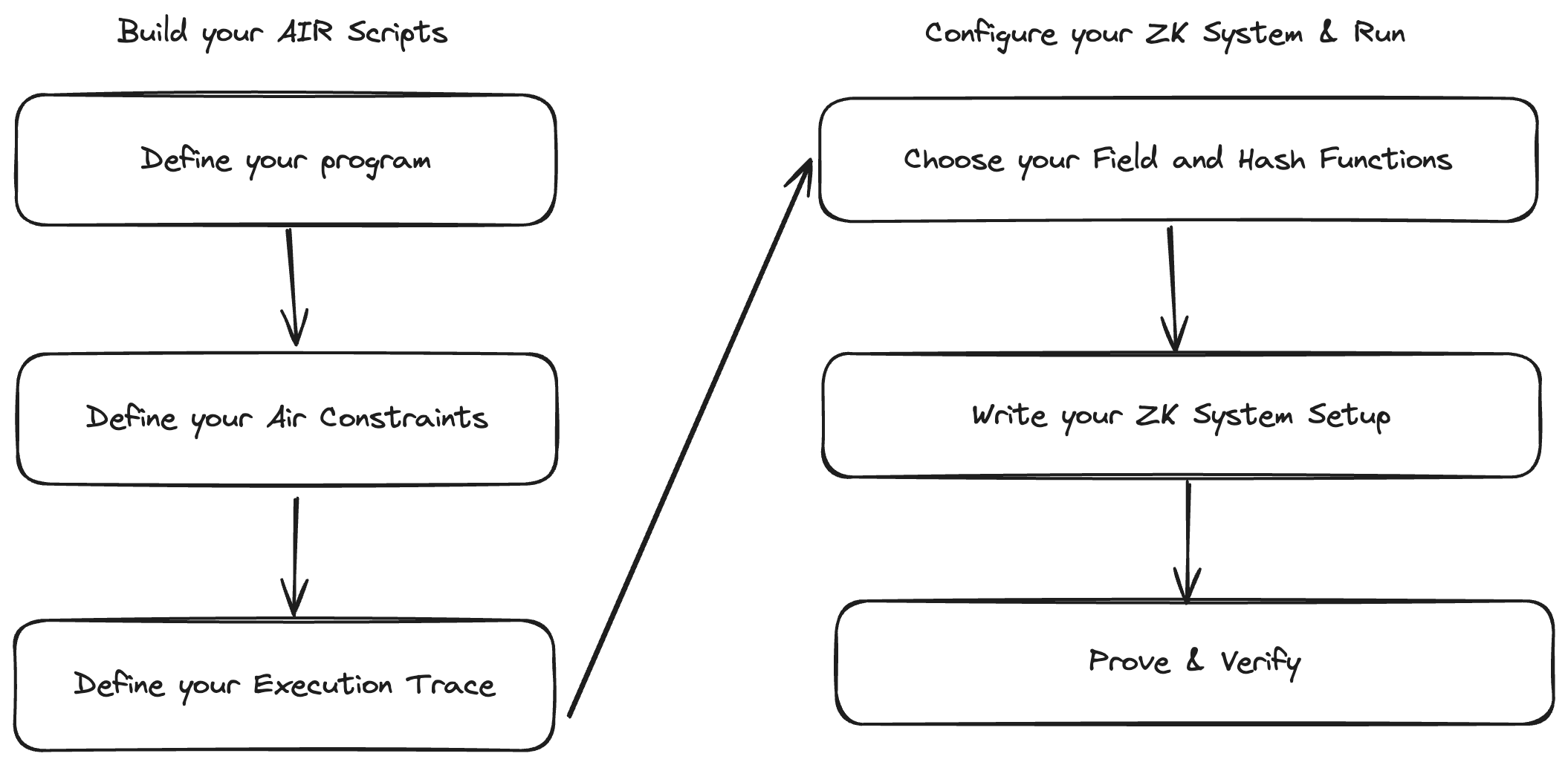

Here’s a TLDR version:

- Define the computation using Algebraic Intermediate Representation (AIR).

- Generate a trace of the computation based on the AIR.

- Utilize efficient finite field implementations for arithmetic operations.

- Apply Generalized Vector Commitment Schemes to create succinct representations of large vectors or polynomials.

- Use polynomial commitment schemes like Circle PCS for compact polynomial representations.

- Perform fast polynomial operations using FFTs and related algorithms.

- Implement the FRI (Fast Reed-Solomon IOP) protocol to prove properties about committed polynomials.

- Employ a challenger mechanism with the Fiat-Shamir heuristic for non-interactive proofs.

- The unified STARK prover combines all components to generate the proof.

- The verifier uses the same components to efficiently check the proof’s validity.

Plonky3’s modular design allows for easy customization and optimization of different components, making it adaptable to various use cases and performance requirements.

If this seems very complicated, don’t worry, these are the underlying workflows of Plonky3 based ZK systems. If you are builders who are using Plonky3, your main job is at Step 1 and Step 2, the rest is just configuration!

Fibonacci AIR Example¶

This example demonstrates how to implement a Fibonacci sequence calculator using Algebraic Intermediate Representation (AIR) in Plonky3. AIR is a way to express computations as polynomial constraints, which is crucial for creating zero-knowledge proofs.

The Fibonacci sequence is a series of numbers where each number is the sum of the two preceding ones, usually starting with 0 and 1. For example: 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, …

We will follow these steps:

Step One: Define your Program¶

First you will need to understand what is the computation you want to prove. In

our case, it is a program that calculates a Fibonacci sequence after n steps.

Then we have requirements of:

- The program must always start with 0 and 1 as the initial inputs

- Each iteration will have two inputs and a output. The second input of the current input will become the first input of the next iteration, and the sum of the current two inputs will become the second input of the next iteration.

- Will iterate

nsteps based on the configuration, and its result will be different according to numbers of steps iterated.

Step Two: Define your AIR Constraints¶

Now that we have our program logic thought out, we will convert it into AIR Constraints.

AIR Constraints are about working with the execution trace, where you can imagine it as a 2D-matrix.

Each row represents the current iteration of the computation, and the width of each row represents the elements that are associated with the whole computation. Basically, in a zkVM context, this could mean that the width of the row is all the registers in this zkVM system, and each row iteration is the transition of all registers from one PC count to next.

Tips on defining your AIR Scripts:

- Define the valid state transition, aka what are the constraints when transitioning from one row to the one below it.

- Define relations among the fields in the same row if needed. Sometimes we have constraints that are only about a single column as well, like if a column is supposed to be 0 or 1 we do x (x - 1) = 0 (or assert_bool() shorthand).

- Define constraints on initial state, if the program has to be run starting with a specific initial state.

- Define constraints on ending state, if the program result needs to be public at the end of execution in this program.

In our example, each row is the current 2 numbers to be added, so the width will be 2. Every row will have a relation of:

- Second field of the current row is the first field of the next row

- The sum of the both fields of the current row is equal to the second field of the next row

We also need to make sure that our program starts with 0 and 1 for the correct execution, as well as, verify the final execution result is the same as expected result.

// Define your AIR constraints inputs via declaring a Struct with relevant inputs inside it.

pub struct FibonacciAir {

pub num_steps: usize, // numbers of steps to run the fibonacci iterations

pub final_value: u32, // precomputed final result after the numbers of steps.

}

// Define your Execution Trace Row size,

impl<F: Field> BaseAir<F> for FibonacciAir {

fn width(&self) -> usize {

2 // Row width for fibonacci program is 2

}

}

// Define your Constraints

impl<AB: AirBuilder> Air<AB> for FibonacciAir {

fn eval(&self, builder: &mut AB) {

let main = builder.main();

let local = main.row_slice(0); // get the current row

let next = main.row_slice(1); // get the next row

// Enforce starting values

builder.when_first_row().assert_eq(local[0], AB::Expr::zero());

builder.when_first_row().assert_eq(local[1], AB::Expr::one());

// Enforce state transition constraints

builder.when_transition().assert_eq(next[0], local[1]);

builder.when_transition().assert_eq(next[1], local[0] + local[1]);

// Constrain the final value

let final_value = AB::Expr::from_canonical_u32(self.final_value);

builder.when_last_row().assert_eq(local[1], final_value);

}

}

Step Three: Define your Execution Trace¶

Third step is to define the function to generate your program’s execution trace. The general idea is to create a function that keeps track of all relevant state of each iteration, and pushes them all into a vector, then at last convert this 1D vector into a Matrix in the dimension that matches your AIR Script’s width.

pub fn generate_fibonacci_trace<F: Field>(num_steps: usize) -> RowMajorMatrix<F> {

// Declaring the total fields needed to keep track of the execution with the given parameter, which in this case, is num_steps multiply by 2, where 2 is the width of the AIR scripts.

let mut values = Vec::with_capacity(num_steps * 2);

// Define your initial state, 0 and 1.

let mut a = F::zero();

let mut b = F::one();

// Run your program and fill in the states in each iteration in the `values` vector

for _ in 0..num_steps {

values.push(a);

values.push(b);

let c = a + b;

a = b;

b = c;

}

// Convert it into 2D matrix.

RowMajorMatrix::new(values, 2)

}

If you are curious how the execution trace looks like, here’s the execution trace of running 8 steps of Fibonacci program.

| col 0 | col 1 |

|---|---|

| 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 2 |

| 2 | 3 |

| 3 | 5 |

| 5 | 8 |

| 8 | 13 |

| 13 | 21 |

We now have both AIR scripts and execution trace ready.

Step Four: Choose your Field and Hash Functions¶

It is time to start the layout of our ZK system. We first start with your

Field and Hash Function of choice.

The choice of field and hash function is crucial for the security and efficiency of your zero-knowledge proof system.

// Your choice of Field

type Val = Mersenne31;

// This creates a cubic extension field over Val using a binomial basis. It's used for generating challenges in the proof system.

// The reason why we want to extend our field for Challenges, is because the original Field size is too small to be brute-forced to solve the challenge.

type Challenge = BinomialExtensionField<Val, 3>;

// Your choice of Hash Function

type ByteHash = Keccak256Hash;

// A serializer for Hash function, so that it can take Fields as inputs

type FieldHash = SerializingHasher32<ByteHash>;

// Declaring an empty hash and its serializer.

let byte_hash = ByteHash {};

// Declaring Field hash function, it is used to hash field elements in the proof system

let field_hash = FieldHash::new(Keccak256Hash {});

Step Five: Write your ZK System Setup¶

This is a very generic setup and it’s ready to be used in all kinds of ZK systems. Generally, you can just copy paste the below code and use it in your own ZK systems.

- First setup is to define the Compression function, it is used in the MMCS (Multi-Merkle Commitment Tree) construction process.

- Use the Field, Field Hash function and the compression function to create

MMCS instance, we shall call this

ValMmcs. - Extend the

ValMmcsinstance created from previous step into the same extension field asChallengefrom Step Four, we call itChallangeMmcs - Define a

Challengerfor Proof Generation (it’s necessary in the PIOP process), which will be used in STARK configuration. Basically creating random challenge inputs for PIOP process. - Define

fri_config, which is later used to createPcs(Polynomial Commitment Scheme). - At last, with

Pcs,Challenge,Challengerprepared, we use them to define our STARK configuration.

// Defines a compression function type using ByteHash, with 2 input blocks and 32-byte output.

type MyCompress = CompressionFunctionFromHasher<u8, ByteHash, 2, 32>;

// Creates a new instance of the compression function.

let compress = MyCompress::new(byte_hash);

// Defines a Merkle tree commitment scheme for field elements with 32 levels.

type ValMmcs = FieldMerkleTreeMmcs<Val, u8, FieldHash, MyCompress, 32>;

// Instantiates the Merkle tree commitment scheme.

let val_mmcs = ValMmcs::new(field_hash, compress);

// Defines an extension of the Merkle tree commitment scheme for the challenge field.

type ChallengeMmcs = ExtensionMmcs<Val, Challenge, ValMmcs>;

// Creates an instance of the challenge Merkle tree commitment scheme.

let challenge_mmcs = ChallengeMmcs::new(val_mmcs.clone());

// Defines the challenger type for generating random challenges.

type Challenger = SerializingChallenger32<Val, HashChallenger<u8, ByteHash, 32>>;

// Configures the FRI (Fast Reed-Solomon IOP) protocol parameters.

let fri_config = FriConfig {

log_blowup: 1,

num_queries: 100,

proof_of_work_bits: 16,

mmcs: challenge_mmcs,

};

// Defines the polynomial commitment scheme type.

type Pcs = CirclePcs<Val, ValMmcs, ChallengeMmcs>;

// Instantiates the polynomial commitment scheme with the above parameters.

let pcs = Pcs {

mmcs: val_mmcs,

fri_config,

_phantom: PhantomData,

};

// Defines the overall STARK configuration type.

type MyConfig = StarkConfig<Pcs, Challenge, Challenger>;

// Creates the STARK configuration instance.

let config = MyConfig::new(pcs);

Step Six: Prove & Verify¶

After the long process of defining the ZK setup, it’s time to use it to prove and verify our program!

// First define your AIR constraints inputs

let num_steps = 8; // Choose the number of Fibonacci steps.

let final_value = 21; // Choose the final Fibonacci value

// Instantiate the AIR Scripts instance.

let air = FibonacciAir { num_steps, final_value };

// Generate the execution trace, based on the inputs defined above.

let trace = generate_fibonacci_trace::<Val>(num_steps);

// Create Challenge sequence, in this case, we are using empty vector as seed inputs.

let mut challenger = Challenger::from_hasher(vec![], byte_hash);

// Generate your Proof!

let proof = prove(&config, &air, &mut challenger, trace, &vec![]);

// Create the same Challenge sequence as above for verification purpose

let mut challenger = Challenger::from_hasher(vec![], byte_hash);

// Verify your proof!

verify(&config, &air, &mut challenger, &proof, &vec![])

Result¶

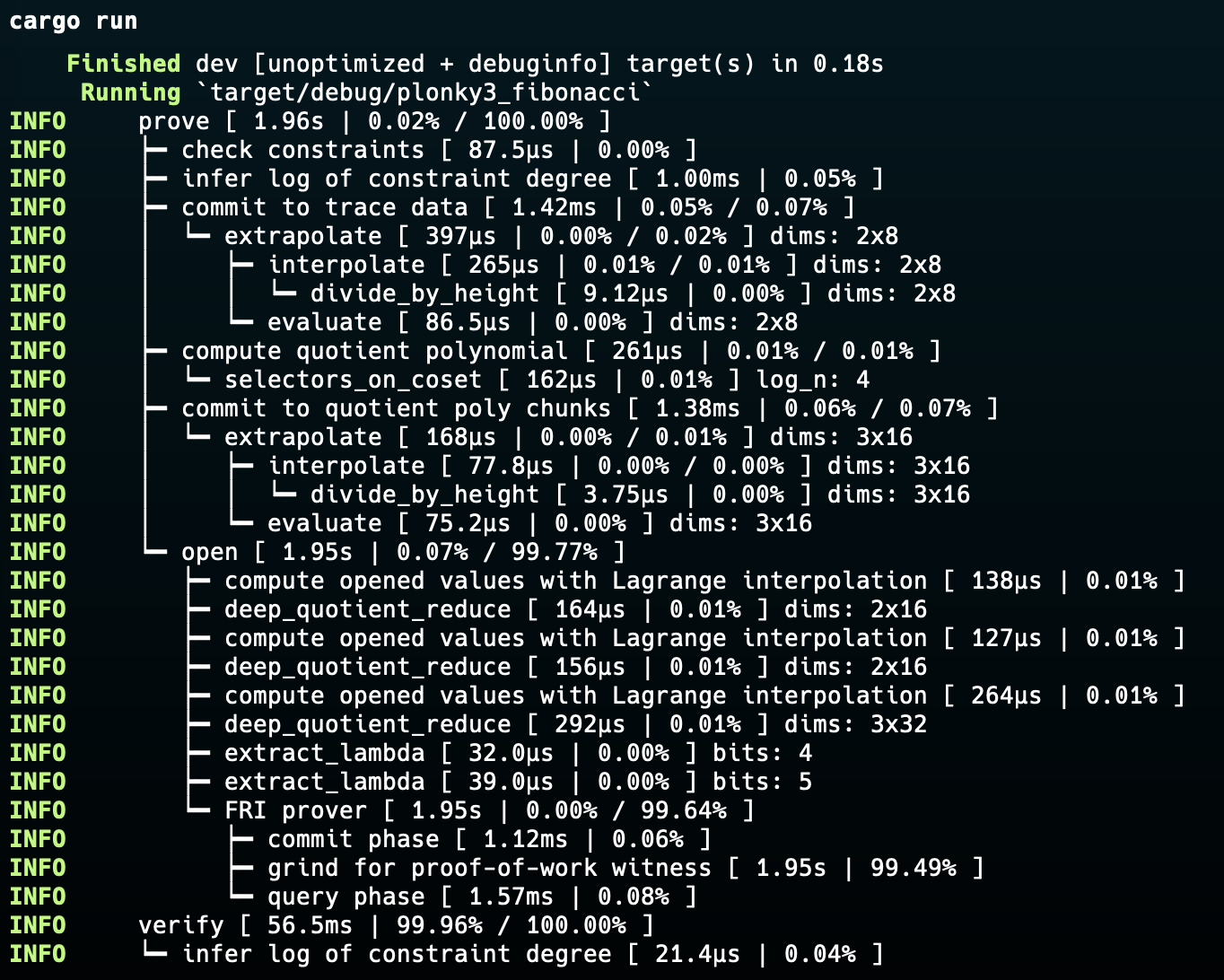

If all of the above code works, this is the output you can expect:

cargo run

Troubleshooting¶

Common issues:

- Incorrect final value: Ensure your Fibonacci calculation matches the AIR constraints

- Proof verification failure: Double-check that the challenger initialization is identical for proving and verifying

Additional Resources¶

There are various other configurations you can explore in Plonky3:

Fields:

- Goldilocks

- BabyBear

- KoalaBear

- Mersenne31

- BN254

Hashes:

- Poseidon

- Poseidon2

- Rescue

- Monolith

- Keccak

- Blake3

- SHA-2

Advanced Examples¶

If you want to check out the implementation of each combination, check the example in keccak-air. This is an example implementation of Keccak (SHA-3) using the Plonky3 framework.