Inclusion arguments

This document describes how Polynomial Identity Language implements Inclusion Arguments.

For most of the programs used in the zkEVM’s Prover, the values recorded in the columns of execution traces are field elements.

In some cases, there may be a need to restrict the sizes of these values to only a certain number of bits. It is therefore necessary to devise a good control strategy for handling both underflows and overflows.

Verify addition of 2-byte numbers¶

The aim in this section is to design a program (and its corresponding PIL code) to verify addition of two integers each of a size fitting in exactly 2 bytes. Any input to the addition program will be considered invalid if it is not an integer in the range [0, 65535].

Naive execution trace¶

Of course, there are many ways in which such a program can be arithmetized. We are going to use a method based on inclusion arguments. The overall idea is to reduce \(2\)-byte additions to \(1\)-byte additions.

Specifically, the program consists of two input polynomials \(\texttt{a}\) and \(\texttt{b}\) where each introduces a single byte (equivalently, an integer in the range [0, 255]) in each row, starting with the less significant byte, for each operand of the sum.

Hence, a new addition is checked in every second row.

The output of the addition between \(1\)-byte words can’t be stored in a single column that only accepts words of \(1\)-byte, since an overflow may occur.

The result of the addition will be split into two columns; \(\texttt{carry}\) and \(\texttt{add}\). Each column accepts only \(1\)-byte words, thereby storing the complete result so that a correct addition between bytes can be defined as:

The below table shows an example of a valid execution trace for this program.

Note that the final sum of each pair of \(2\)-byte numbers, in the above table, is composed of the last \(\texttt{carry}\) value and the last two \(\texttt{add}\) values, from the most significant to the least significant (going from left to right).

For example, \(\texttt{0x3011} + \texttt{0x4022} = \texttt{0x007033}\). Similarly, \(\texttt{0x00ff} + \texttt{0xffee} = \texttt{0x0100ed}\).

Observe that \(\text{Eqn. 9}\) is not satisfied in row 4, because the \(\texttt{carry}\) value raised in the third row must be added to the \(1\)-byte addition at row 4.

The problem with this design is that there’s no direct way to introduce the previous value of \(\texttt{carry}\) in the PIL code.

Adding an extra polynomial¶

There is a need to introduce another polynomial, call it \(\texttt{prevCarry}\), which contains a shifted version of the value in the \(\texttt{carry}\) polynomial.

More specifically, we add the following constraint to ensure that \(\texttt{prevCarry}\) is correctly defined:

There is another snag here. According to \(\text{Eqn.10}\), the previous \(\texttt{carry}\) value could affect two different 2-byte additions. That is, two non-related operations should not be linked via carries.

A selector polynomial can be used to separate values of \(\texttt{carry}\) from one addition to another. We use \(\texttt{RESET}\) as previously used.

\(\texttt{RESET} = 1\) for every odd row index, and \(\texttt{RESET} = 0\) otherwise.

The execution trace is now adjusted as follows,

Following this logic, we can now derive the final (and accurate) constraint:

The PIL code can now be written as follows:

include "config.pil";

namespace TwoByteAdd(%N);

pol constant RESET;

pol commit a, b;

pol commit carry , prevCarry , add;

prevCarry ' = carry;

a + b + (1-RESET)*prevCarry = carry*2**8 + add;

Addition of n-byte numbers¶

Similarly to the Multiplier example of the previous sections, it is worth mentioning that by changing only the \(\texttt{RESET}\) polynomial (and not the PIL itself), it is possible to arithmetize the program in such a way that generic \(n\)-byte additions can be verified.

In such cases, \(\texttt{RESET} = 1\) for the first \(n-1\) rows of each operation, and \(\texttt{RESET} = 0\) in the \(n\)-th row of the operation.

Up to this point, one can think that the constraint in \(\text{Eqn. 11}\) restricts sound representation of the program. However, since we are working over a finite field, it is not.

For example, the following execution trace is valid, as it satisfies all the constraints, but does not correspond to a valid computation:

The above table gives a concrete example of how to work around any restrictions of the current program.

Nonetheless, the introduction of more bytes in either column does not break the intention of this program, which was designed to only deal with byte-sized columns. It is strictly necessary to enforce that all the evaluations of committed polynomials be correct.

An inclusion argument is used for this purpose.

Inclusion argument¶

Given two vectors, \(\texttt{a} = (a_1, . . . , a_n) \in \mathbb{F}^n_p\) and \(\texttt{b} = (b_1,...,b_m) \in \mathbb{F}^m_p\), it is said that,

In other words, if one thinks of \(\texttt{a}\) and \(\texttt{b}\) as multisets and reduce them to sets (by removing the multiplicity), then \(\texttt{a}\) is contained in \(\texttt{b}\) if \(\texttt{a}\) is a subset of \(\texttt{b}\). See this document for more details on multisets and Plookup.

A protocol \((\mathcal{P},\mathcal{V})\) is an inclusion argument if the protocol can be used by \(\mathcal{P}\) to prove to \(\mathcal{V}\) that one vector is contained in another vector.

In the PIL context, the implemented inclusion argument is the same as the \(\text{Plookup}\) method provided in [GW20], also discussed here. Other “alternative” method exists such as the \(\text{PlonkUp}\) described in [PFM+22].

An inclusion argument is invoked in PIL with the “\(\texttt{in}\)” keyword.

Specifically, given two columns \(\texttt{a}\) and \(\texttt{b}\), we can declare an inclusion argument between them using the syntax \(\{\texttt{a}\}\ \texttt{in} \ \{\texttt{b}\}\), where \(\texttt{a}\) and \(\texttt{b}\) do not necessarily need to be defined in different programs.

For instance, the PIL code for a program called \(\texttt{A}\), with an inclusion argument is as follows.

include "config.pil";

namespace A(%N);

pol commit a, b;

{a} in {b};

namespace B(%N);

pol commit a, b;

{a} in {Example1.b};

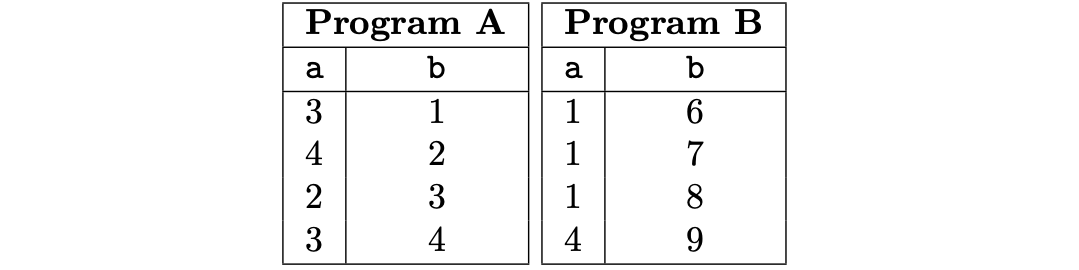

A valid execution trace (with \(\texttt{N} = 4\)) for the above example is shown in the below table.

Generalized inclusion arguments¶

In PIL we can also write inclusion arguments not only over single columns but over multiple columns. That is, given two subsets of committed columns \(\mathtt{a_1}, \dots , \mathtt{a}_m\) and \(\texttt{b}_1, \dots , \texttt{b}_m\) of some program(s) we can write as,

to denote that the rows generated by columns \(\mathtt{a}_1, \dots , \mathtt{a}_m\) are included (as sets) in the rows generated by columns \(\{\mathtt{b}_m , \dots , \mathtt{b}_m\}\).

A natural application for this generalization shows that a set of columns that a program repeatedly computes, probably with the same pair of inputs/outputs, an operation such as \(\texttt{AND}\), where the correct \(\texttt{AND}\) operation is carried on a distinct program (see the following example).

include "config.pil";

namespace Main(%N);

pol commit a, b, c;

{a,b,c} in {in1,in2,xor};

namespace AND(%N);

pol constant in1, in2, and;

Following on with the previous “TwoByteAdd” Addition program example, one can construct four new constant polynomials; \(\mathtt{BYTE\_A}\), \(\mathtt{BYTE\_B}\), \(\mathtt{BYTE\_CARRY}\) and \(\mathtt{BYTE\_ADD}\); containing all possible byte additions.

The execution trace of these polynomials can be constructed as follows:

Recall that there is no need to enforce constraints between these polynomials since they are constant and therefore, publicly known.

As to whether the tuple \((\texttt{a}, \texttt{b}, \texttt{carry}, \texttt{add})\) is contained in the previous table, an inclusion argument can be utilized and thus ensure a sound description of the program. The inclusion constraint is not only ensuring that all the values are single bytes, but also that the addition is correctly computed.

Consequently, none of the rows of the above table is contained in the previous table, marking them as non-valid rows.

Of course, this introduces some redundancy into the PIL code, because the byte operation is being checked twice. First with the polynomial constraint, and second with the inclusion argument. However, the polynomial constraint cannot be dropped as it is necessary for linking rows belonging to the same addition.

The following line of code completes the PIL for the \(\texttt{TwoByteAdd}\) program:

{a, b, carry, add} in {BYTE_A, BYTE_B, BYTE_CARRY, BYTE_ADD};

To sum up, the following PIL program correctly describes the complete \(\texttt{TwoByteAdd}\) program:

include "config.pil";

namespace TwoByteAdd(%N);

pol constant BYTE_A, BYTE_B, BYTE_CARRY, BYTE_ADD;

pol constant RESET;

pol commit a, b;

pol commit carry, prevCarry, add;

prevCarry ' = carry;

a + b + (1 - RESET)*prevCarry = carry*2**8 + add;

{a, b, carry, add} in {BYTE_A, BYTE_B, BYTE_CARRY, BYTE_ADD};

Compiling this .pil file, we get the following debugging message:

Input Pol Commitmets: 5

Q Pol Commitmets: 0

Constant Pols: 5

Im Pols: 0

plookupIdentities: 1

permutationIdentities: 0

connectionIdentities: 0

polIdentities: 3

Observe that \(\texttt{plookupIdentities}\) counts the number of inclusion arguments used in the PIL program (one in our example).

Avoiding redundancy¶

Further modifications can be added to avoid redundancy in the PIL. This can be achieved by introducing another constant polynomial \(\mathtt{BYTE\_PREVCARRY}\).

In this case, the constant polynomials’ table formed by the polynomials; \(\mathtt{BYTE\_A}\), \(\mathtt{BYTE\_B}\), \(\mathtt{BYTE\_PREVCARRY}\), \(\mathtt{BYTE\_CARRY}\) and \(\mathtt{BYTE\_ADD}\); should be generated by iterating among all the possible combinations of the tuple \(\big(\mathtt{BYTE\_A},\ \mathtt{BYTE\_B},\ \mathtt{BYTE\_PREVCARRY} \big)\) and computing \(\mathtt{BYTE\_CARRY}\) and \(\mathtt{BYTE\_ADD}\) accordingly in each of the combinations.

The table only becomes twice bigger because \(\mathtt{BYTE\_PREVCARRY}\) is binary.

A summary of how the table looks like with the new changes is already in the table below:

In addition, recall that we only have to take into account \(\texttt{prevCarry}\) whenever \(\texttt{RESET}\) is \(0\).

PIL is flexible enough to consider this kind of situation involving Plookups. To introduce this requirement, the inclusion check can be modified as follows:

{a, b, (1 - RESET)*prevCarry, carry, add} in {BYTE_A, BYTE_B, BYTE_PREVCARRY, BYTE_CARRY, BYTE_ADD };

With this modification, the PIL program becomes:

include "config.pil";

namespace TwoByteAdd(%N);

pol constant BYTE_A, BYTE_B, BYTE_PREVCARRY, BYTE_CARRY , BYTE_ADD;

pol constant RESET;

pol commit a, b;

pol commit carry, prevCarry, add;

prevCarry' = carry;

{a, b, (1 - RESET)*prevCarry, carry, add} in {BYTE_A, BYTE_B, BYTE_PREVCARRY, BYTE_CARRY, BYTE_ADD};