Execution

Polygon Miden is an Ethereum Rollup. It batches transactions - or more precisely, proofs - that occur in the same time period into a block.

The Miden execution model describes how state progresses on an individual level via transactions and at the global level expressed as aggregated state updates in blocks.

Transaction execution¶

Every transaction results in a ZK proof that attests to its correctness.

There are two types of transactions: local and network. For every transaction there is a proof which is either created by the user in the Miden client or by the operator using the Miden node.

Transaction batching¶

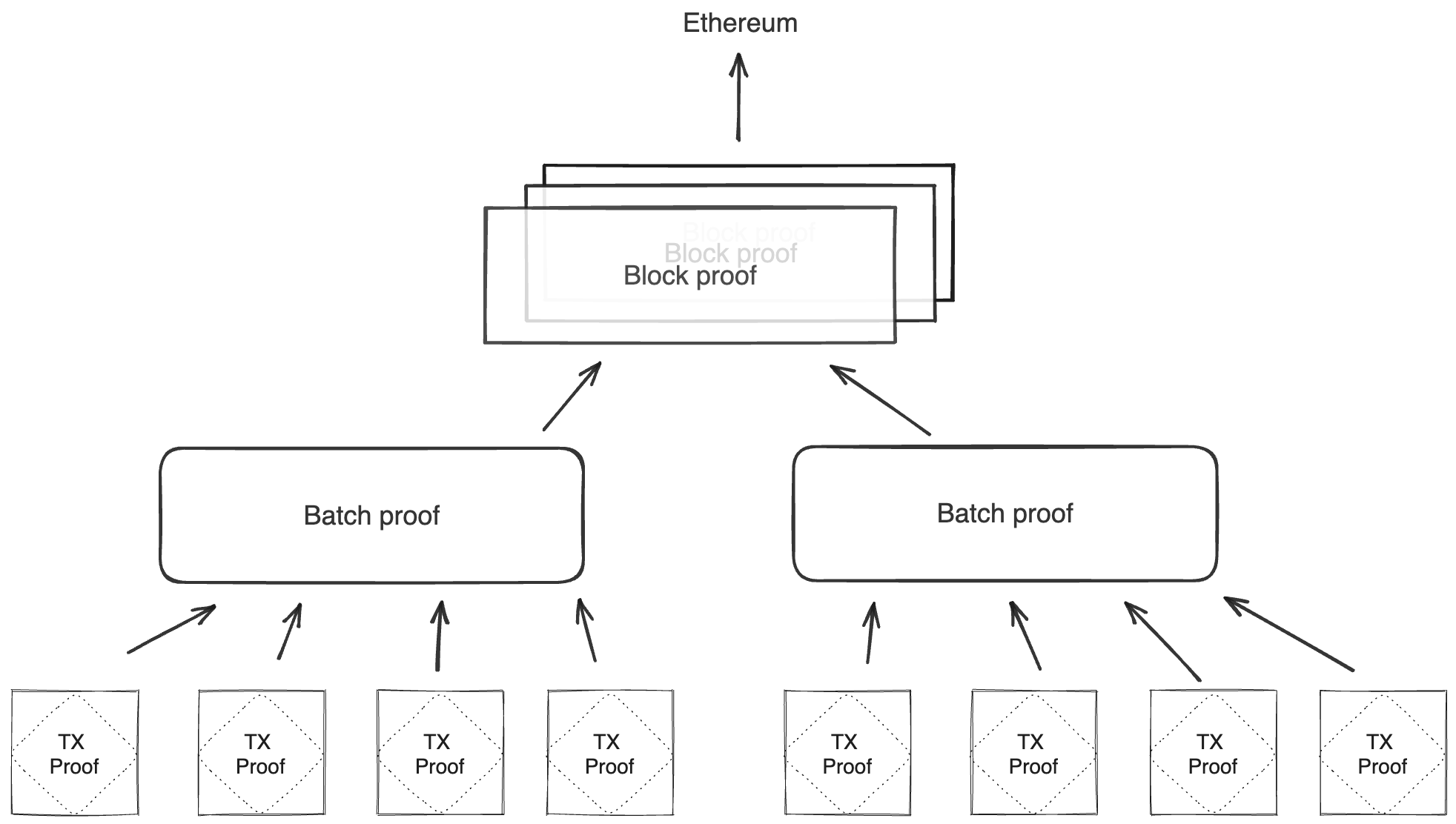

To reduce the required space on the Ethereum blockchain, transaction proofs are aggregated into batches. This can happen in parallel on different machines that need to verify several proofs using the Miden VM and thus creating a proof.

Verifying a STARK proof within the VM is relatively efficient but it is still costly; we aim for 216 cycles.

Block production¶

Several batch proofs are aggregated into one block. This cannot happen in parallel and must be done by the Miden operator running the Miden node. The idea is the same, using recursive verification.

State progress¶

Miden has a centralized operator running a Miden node. Eventually, this will be a decentralized function.

Users send either transaction proofs (using local execution) or transaction data (for network execution) to the Miden node. Then, the Miden node uses recursive verification to aggregate transaction proofs into batches.

Batch proofs are aggregated into blocks by the Miden node. The blocks are then sent to Ethereum, and once a block is added to the L1 chain, the rollup chain is believed to have progressed to the next state.

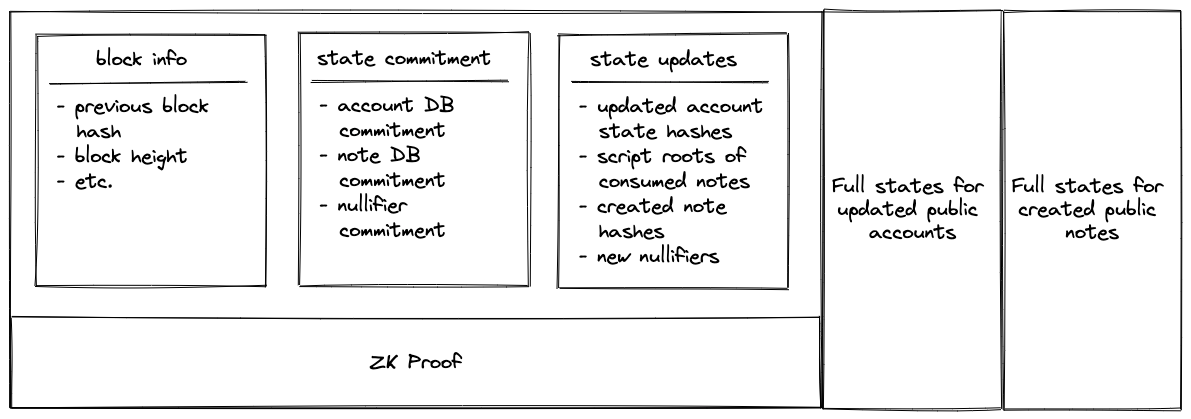

A block produced by the Miden node looks something like this:

Block contents

- state updates only contain the hashes of changes. For example, for each updated account, we record a tuple

([account id], [new account hash]). - ZK Proof attests that, given a state commitment from the previous block, there was a sequence of valid transactions executed that resulted in the new state commitment, and the output also included state updates.

- The block also contains full account and note data for public accounts and notes. For example, if account

123is an updated public account which, in the state updates section we’d see a records for it as(123, 0x456..). The full new state of this account (which should hash to0x456..) would be included in a separate section.

Verifying valid block state¶

To verify that a block describes a valid state transition, we do the following:

- Compute hashes of public account and note states.

- Make sure these hashes match records in the state updates section.

- Verify the included ZKP against the following public inputs:

- State commitment from the previous block.

- State commitment from the current block.

- State updates from the current block.

The above can be performed by a verifier contract on Ethereum L1.

Syncing to current state from genesis¶

The block structure has another nice property. It is very easy for a new node to sync up to the current state from genesis.

The new node would need to do the following:

- Download only the first part of the blocks (i.e., without full account/note states) starting at the genesis up until the latest block.

- Verify all ZK proofs in the downloaded blocks. This is super quick (exponentially faster than re-executing original transactions) and can also be done in parallel.

- Download the current states of account, note, and nullifier databases.

- Verify that the downloaded current state matches the state commitment in the latest block.

Overall, state sync is dominated by the time needed to download the data.